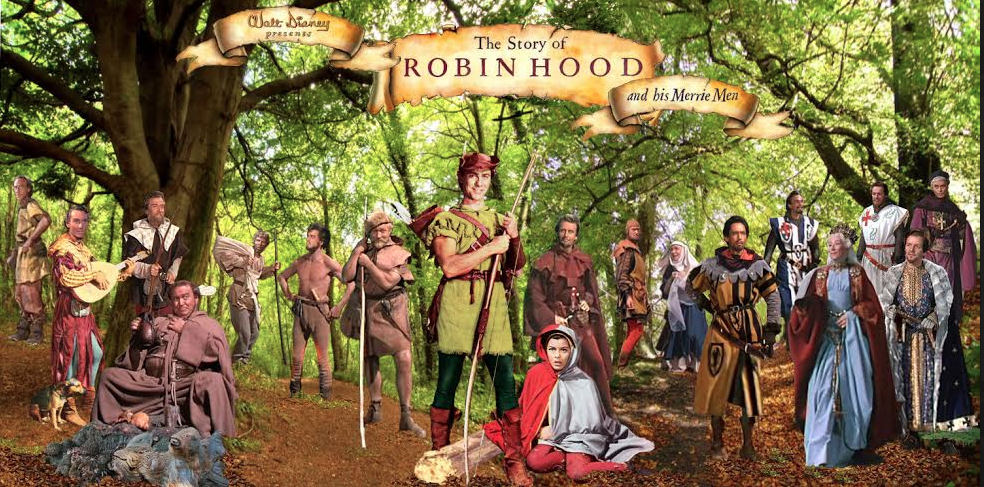

A while ago I posted an article called ‘Meet Clement of the Glen’ in which I explained how my interest in the search for Robin Hood was inspired by Disney’s live-action movie the ‘Story of Robin Hood’ and the classic TV series with Richard Greene. I also explained how my interest grew one day in my college library, when I read an article about the amazing discovery by Joseph Hunter of a Robin Hood in the Wakefield Court Rolls. So I thought it was time to explain some of the facts behind this fascinating discovery and how it inspired many later quests for the illusive outlaw.

It was the discoveries of the Rev. Joseph Hunter F.S.A., in ancient public records that first excited the scholars, threw new light on a possible identity for the famous outlaw and an authentic historical setting for the early Robin Hood ballads.

Joseph Hunter was born in Sheffield on 6th February 1783, the son of Michael Hunter, a cutler. His mother died while Joseph was young and he was placed under the guardianship of the Rev. Joseph Evans, a Presbyterian Minister. He was Educated at Attercliffe and later studied theology at New College in York, becoming a Unitarian Minister in Bath from 1809 until 1833. It was during this period he had two scholarly histories about Hallamshire (South Yorkshire) published.

Hunter’s early interest in antiquarian pursuits and studies of the history of his native county eventually led to a professional career when, in 1833, he was appointed a sub-commissioner of the Records Commission and he moved to London. From 1838 to his death he became an assistant keeper of the new Public Record Office. It was during his distinguished career he edited many philological books, diaries, and catalogues and after his death on 9th May 1861, the British Museum, realising its value, purchased a large amount of his manuscript collection. This included ‘Families Minorum Gentium' - a volume of some 650 pages completely filled with the pedigrees, of mainly Yorkshire, Derbyshire, Cheshire, and Lancashire families. The Rev. Joseph Hunter was buried in St. Mary’s Churchyard, Ecclesfield in Sheffield Yorkshire.

It was no doubt during his research of the government records and the ancient manuscripts of Yorkshire that he turned his attention to the problem of Robin Hood and in 1852 the fourth and last of his series of ‘Critical and Historical Tracts’ was published. It was titled ‘The Great Hero of the Ancient Minstrelsy of England, Robin Hood his Period etc. Investigated and Perhaps Ascertained.’

He began his paper by rebuking those who:

‘………….acting in the wild humour of the present age, which is to put everything that has passed into doubt, and turn the men of former days into myths, would represent this outlaw living in the woods as a mere creature of the imagination of men living in the depths of antiquity. So far back that we know neither when nor where, Hudekin because his name was Hood, and Robin Goodfellow, because his name was Robert………..

‘………I dismiss these theorists to that limbo of vanity there to live with all those who would make all remote history fable, who would make us believe that everything which is good in England is a mere copy of something originated in countries eastward of our own, and who would deny the English nation in past ages all skill and all advancement in literature, or in the arts of sculpture and architecture. Even a much more reasonable conjecture I dismiss also: namely that the character of this hero is a mere creation of some poetical mind, who saw the fitness of the outlaw in the forest among characters suitable for his muse.’

Firstly, Hunter points out that Langland’s reference to Robin Hood in ‘Piers Plowman’ seems to indicate that during the reign of Richard III he was regarded as a real person. He then shows how the reference in the ‘Geste of Robyn Hode’’ to ‘the Sayles,’ the situation of ‘Robin Hood’s Stone' on the Great North Road and the notoriety of Barnsdale (Robin’s location in the Geste) seemed to indicate that the origins of the tales stemmed from the West Riding of Yorkshire.

‘Robyn stode in Bernesdale,

And lenyd hym to a tre.’

He demonstrated from record evidence that it was necessary in the early fourteenth century for travelers to have a guard when they passed through Barnsdale. When King Edward I’s army seized William de Lamberton the Bishop of St. Andrews, Robert Wishart the Bishop of Glasgow and Henry Abbot of Scone and sent them south as prisoners, the accounts of payments show that a guard of eight to twelve archers were used. But on the road from Pontefract to Tickhill the guard was raised to twenty ‘on account of Barnsdale.

'And walke up to the Saylis,

And so to Watlinge Strete.'

Hunter’s impressive detective work continued with his identification of ‘the Saylis’ which is mentioned in the ‘Geste’ as a small tenancy, a tenth of a knight’s fee, in the manor of Pontefract. When considering Robin’s instructions to Little John to ‘walke up to the Saylis and so to Watlinge Strete,’ Hunter said there is in these few words, ‘something which impresses a person acquainted with the district with the conviction of the reality of these events.’ ‘Watlinge Strete’ he said was ‘doubtless the Roman highway which crosses Barnsdale.’

'Thou shalt with me to grene wode,

Without ony leasynge,

Tyll that I have gete us grace

Of Edwarde, our comly kynge.'

In the ‘Geste of Robyn Hode’ the king comes to Nottingham and inquires about the outlaw. The monarch is furious to see his herds of deer depleted and swears, ‘I wolde I had Robyn Hode, with eyen I might hym se.’ Eventually a forester suggests that the only way to find him is for the king to disguise himself and five of his knights in monks’ clothing and be guided by himself to Robin’s haunts.

It was Hunter who first proposed Edward II (1284-1327) as the ‘comly kynge’ of the ‘Geste.’ ‘We know moreover that King Edward the Second did make a progress in Lancashire and only one,’ he says. ‘The time was in the autumn of his seventeenth year, AD. 1323. The reader may find what is sufficient proof in the ‘teste’ of various of the king’s writs, printed in the ‘Foedera’. Altogether he was that year in the north from the month of April till 17th of December, when he set out on his way to Kenilworth, where he meant to spend Christmas in one of the castles of his late great enemy, the Earl of Lancaster, whom he had not long put to death.’

'All the compasse of Lancasshyre

He went both ferre and nere,

Tyll he came to Plomton Parke,

He faylyd many of his dere.'

In March of 1323 Edward II ordered investigations into raids in the Royal Forests, particularly of Staffordshire and southern Derbyshire. There were also disturbances in the Forest of Pickering.

The intriguing circuit of Edward II in the latter half of 1323, discovered by Hunter, shows that he travelled to York via Newham, Rockingham, Oakham and Newark and arrived at York on May 1st where he stayed at the Archbishop’s Palace. After living some time in Holderness in York and at Hadlesey, Cowick and Thorne, his progress took him to Rothwell between Wakefield and Leeds visiting Plumpton Park near Knaresborough from May 16th to the 21st. He then moved in August to Kirkham Abbey and arrived at Pickering Castle on the 8th. During the king’s stay over twenty people were accused of venison trespasses since Thomas of Lancaster’s death.

In September he stayed at Wherlton Castle in the country about Richmond and Jervaulx Abbey. On 22nd of September he was at Haywra Park, the forest of Knaresborough and then moved on to Lancashire (the King’s Bench also travelled to Lancashire to try offenders). At the Manor of Upholland, Edward heard many cases of Forest transgression; they included the names of Earls, Knights and ordinary tenants.

On 4th October he was at Ightenhill Park, near Cltheroe and then onto Blackbourne, Holand, Kirkby and Liverpool. On the 3rd November he moved on to the monastery of Vale Royal, and then stayed at Sandbach, Newcatle-under-Line, Coxden, Langford and Dale Abbey.

Edward II arrived at Nottingham on 9th November and stayed till the 23rd.

'The kynge came to Notynghame

With knyghtes in gret araye.'

‘There is a correspondence in all this,’ Hunter says, ‘which I venture to think is not quite accidental.’

'Had Robyn dwelled in the kynges courte,

But twelve monethes and thre.'

Halfway through his book Joseph Hunter went on to explain his most significant find:

‘Now it will scarcely be believed, but it is, nevertheless, the plain and simple truth, that in the documents preserved in the Exchequer containing accounts of the expenses of the king’s household, we find the name of ‘Robyn Hode,’ not once, but several times occurring, receiving, with about eight and twenty others, the pay of 3d. a day, as one of the ‘vadlets, porteurs de la chambre’ of the king. Whether he was some other person who chanced to bear the same name, or that the ballad-maker has in this related what was mere matter of fact, it will become no one to affirm in a tone of authority. I for my part believe it is the same person. The date of the Lancashire Progress fixes the period of Robin’s reception into the king’s service as just before Christmas, 1323, and the first time that the name of ‘Robyn Hode’ is found in the ‘Jornal de la Chambre’ is from 16th April to 7th July 1324. The first entry in which the name occurs is:

On 25th April: Henri Lawe, Colle de Ashruge, Will de Shene, Joh. Petmari, Grete Hobbe, Litell Colle, Joh. Edrich, ROBYN HOD, Simon Hod, Robert Trasshe, [and nineteen others].

On May 17th: To Robert Hod and thirty-one other porters for wages from 22nd April to May 12th, less five days for Robert Hod because of absence.

On June 10th: To Robyn Hod twenty-seven days wages, less one day deducted for absence.

On June 30th: Twenty six porters received their wages but Robyn Hod received nothing.

On July 22nd: To Robert Hood and six other vadletz being with the king at Fulham by his command from the 9th day of June arrears of wages at 3d a day for twenty one day’s pay.

On 21st August: Payment is made to 'Jack Ede, Colle Ashruge, Robin Dycker, Lutel Colle, Grete Hobbe, Jack Becker, Jack Langworth, Robyn Baker, Robyn Curre, Jack Chertsey’ and others received 28 days pay, four days were deducted from Simon and eight days from Robin for non-attendance.

On October 6th: Robyn Hod received full pay.

On 21st October: There was no payment for Robin, who had been absent the whole period.

From October 21st to November 24th: the Clerk of the Chamber paid Robyn Hod for 35 days, but deducted seven days because of absence.

On 22nd November: ‘To Robyn Hod formerly one of the porters because he can no longer work, five shillings as a gift by commandment.

Edward II (1307-1327)

'Alas! Then sayd good Robyn,

Alas and well a woo.

Yf I dwele lenger with the kynge,

Sorowe wyll me sloo.'

‘There is in all this,’ says Hunter, ‘perhaps as much correspondency as we can reasonably expect between the record and the ballad.

In the final part of his groundbreaking book Hunter concentrated on trying to find a link with the Robyn Hod in the king’s service and a Robert Hood of Wakefield who he had discovered in the manor court rolls.

In the ‘9th year of Edward son of Edward,’ Hunter had found, recorded in the manuscripts, that an Amabel Brolegh sued Robert Hood for ‘7s issuing from a rood of land which the said Robert demised to the same Amabel for the term of six years which he was not able to warrant her.’

'Yet he was begyled, iwys,

Through a wicked woman,

The pryoresse of Kyrkely,

That nye was of hys kynne.'

In the following year the Wakefield Court Rolls revealed to Hunter the name of Robert Hood’s wife, she was called Matilda. (It was in 1598 that the Tudor playwright Anthony Munday transformed Maid Marian into Matilda in his two plays, ‘The Downfall’ and ‘The Death of Robert Earl of Huntington.’)

He also thought he had a found a link to the wicked prioress who was said to have been of ‘Robin’s kin.’ In a parcel of deed dated 1344 is a grant from Henry, son of Amabil of Wolflay-Morehouse, to Adam, son of Thomas de Staynton. An Elizabeth de Staynton was placed in Kirklees Priory and became prioress in c.1346-1347.

So Hunter summarised:

‘[That Robin Hood] was one of the Contrariantes of the reign of Edward II and living in the early reign of King Edward III, but whose birth is carried back into the reign of King Edward I, and fixed in the decennary period, 1285 to 1295: that he was born in a family of some station and respectability seated at Wakefield or in the villages around; that he, as many others partook of the popular enthusiasm [in Lancaster’s cause, and after the defeat of his overlord took to robbery in Barnsdale]; that he continued this course for about twenty months, April 1322 to December 1323...............The king, possibly for some secret and unknown reason, not only pardoned him all his transgressions, but gave him the place of one of the ‘vadlets, porteurs de la chamber,’ in the royal household, which appointment he held for about a year, when the love for the unconstrained life he had led, and for the charm of the country returned, and he left the court and betook himself again to the greenwood.’

This was the case put forward by Joseph Hunter and was it hailed as a tremendous success by many academics, but also given short shrift from others, including Francis Child the editor on ‘English and Scottish Ballads.’ ‘To detect ‘a remarkable coincidence between the ballad and the record,’ Child said, ‘requires not only theoretical prepossession, but an uncommon insensibility to the ludicrous.’

But Hunter’s research was taken up again in 1944 by the local historian J.W. Walker and more information was discovered about the Robert Hood of Wakefield. Ten years later by P. V. Harris continued Hunter's investigation and found more names that could be linked with the ballads. 1985 saw the publication of ‘Robin Hood An Historical Enquiry’ by Professor John Bellamy. This was a re-assessment of the historical research into Robin Hood including the Wakefield Court Rolls and more discoveries of ‘personae’ of the Geste including a possible Sheriff of Nottingham. The books about their discoveries will also be featured later, on my blog.

Joseph Hunter’s discoveries still remain as fascinating and as controversial today as they did when his book was first published in 1852. It later opened the rather petty argument between Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire over ‘Robin Hood Country’ as historical interest grew away from Sherwood and became more focused on Yorkshires links with the outlaw. For me, his work opened up an amazing quest for Robin Hood, which continues to encompass so many paths in history. This includes an interest in the reign of the much maligned Edward II. Who was according to Hunter, the ‘comly kynge’ who pardoned the Robin Hood of Wakefield and employed him as a royal porter.

I thoroughly recommend four sites on the web, owned by Jules Frusher (Lady D) and Kathryn, which cover with extraordinary detail the reign of Edward II. They are all in my blog list; Kathryn’s blog is Edward II and her informative web site is King Edward II. Lady Despensers Scribery and Lady D’s web site Hugh Despenser The Younger are equally well researched and very interesting.

To read about the medieval ballad, a 'Geste of Robyn Hode,' and others, please click on the label 'Robin Hood Ballads' and scroll down.

Could King Edward II have met the legendary outlaw Robin Hood? What do you think?