|

| Scathelock is put in the stocks |

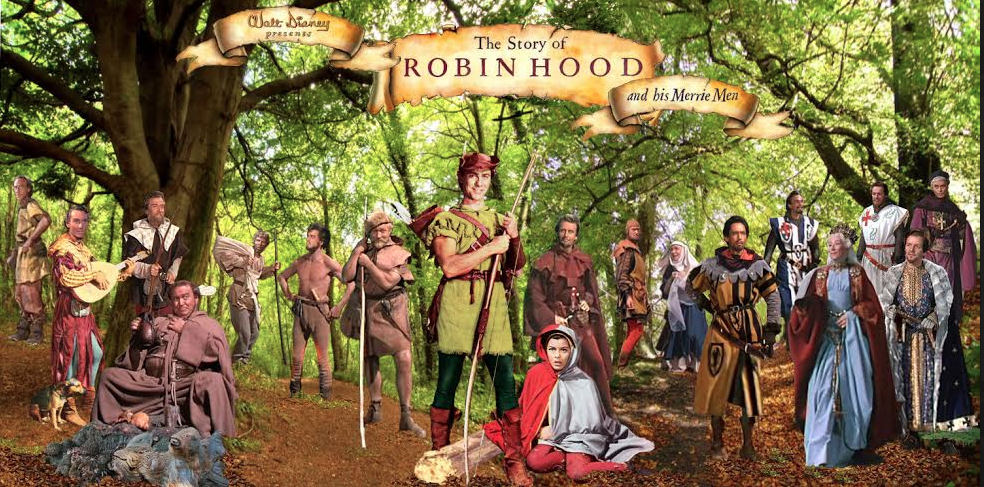

Neil has been a regular contributor to this blog for many years and shown above is a still that he recently sent to me. It is of course from Walt Disney's Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men (1952). I love seeing these images from my favourite movie. When concentrating on the film's

It was Carmen Dillon (1908-2000) who was given the job of art director on Robin Hood by Walt Disney. She had a fine reputation on both sides of the Atlantic for imagination and artistic flair allied to a practical approach to set design and construction, which had been evident in her art direction of some of the biggest and most highly praised period films made in Britain at that time, including Henry V and Hamlet, for which she won her Oscar.

|

| Carmen Dillon discusses the design of Nottingham Square |

Catherine O'Brien in her article, Carmen Over Came Prejudice

..........And Put On Her Slacks, gives a detailed account of this remarkable woman and her work on Robin Hood:

"Small and neat of figure, with greying hair and light blue eyes, Carmen Dillon was born in Ireland. After she had qualified as an architect, she became greatly attracted by the artistic possibilities of film set design and set out to get a job which would train her in this field. It is strange to reflect that this happened only fifteen years ago and yet at this time no one in film studios would take the idea of a woman art director seriously.

|

| Carmen discussing a castle interior |

Anyone knowing Carmen Dillon, however, would realise that such an attitude would only serve to strengthen her determination to attain her objective. Eventually, she obtained toe-hold in a studio at Wembley, as an assistant in the art department. Even then petty restrictions beset her at every turn. She was not permitted to go on a set in slacks and was forbidden to discuss her work with the men in the studio workshops and stages. After a few weeks of making the best of this difficult situation, Carmen was asked to take over the work of an art director who had fallen ill on the eve of a production. By proving her undoubted talent and aptitude for production design she was able to overcome the prejudice which had hitherto hampered her career.

|

| The townsfolk turn on the Sheriff |

On Walt Disney’s Robin Hood, Carmen was in control of a staff of over two hundred men, who accepted her advice and judgement with the same respect and deference as they would accord to any male art director. Among the technicians, she has earned, through her skill and tact, a reputation for knowing exactly what she wants, without fuss or muddle. She carries all the details of planning and building the sets in her head and has a remarkable knack of foreseeing and thus forestalling building problems.

Before the stage is set for the actors, the lighting cameraman and the director, Carmen plans the work, step by step, with fastidious detail. In the case of Robin Hood, the first step was research, to ensure that the pictorial effect should have a truly authentic 12th-century keynote.

|

| Collecting for the King's ransom in Nottingham Square |

Two of the twenty-five interior sets designed by Carmen Dillon for Walt Disney’s Robin Hood serve to illustrate the immense research and artistry with which she conjured up the background and atmosphere of 12th-century England. One of- Nottingham Square, in the reign of Richard Lionheart-was, constructed both on Denham lot and on one of the studio stages-to cater for both units.

Three sides of an irregular square were surrounded by houses, some half-timbered and all pre-fabricated in the plasterer's shop under the direction of Master Plasterer Arthur Banks. The houses and shops made of plaster and wattle (which was, in fact, the building material of that period) had every appearance of solid antiquity in despite of their backing of tubular steel scaffolding. Most imposing was the Sheriff’s house, with its carved arches and steep outside staircase. Thatching was carried out by one of Britain’s oldest surviving craftsmen in this line Mr A. Gilder of Stoke Poges.

The centre of the square was filled with wattle hurdles and pens in which were enclosed game and produce of every type. By the time the stars, featured players and extras-numbering up to two hundred-had taken their place in the square it was hard to imagine a more convincing reproduction of life in 12th century England. It is in this setting that Robin Hood and his men ride in from the forest to rescue a poacher and a farmer who are suffering at the hands of the Sheriff of Nottingham and succeed in turning the tables on their hated persecutor.

|

| The Outlaws receive a signal |

One of the most important sets in the film is the Sherwood Forest camp where Robin Hood and his Merry Men live in outlawry, in their woodland hideout. Some weeks before the film, Carmen accompanied a research party including producer Perce Pearce, scriptwriter Larry Watkin, and film star Richard Todd to Nottingham and returned laden with photographs of every relic of Robin Hood days, which would help her construct the original setting at Denham Studios.

In what little remains of the original Sherwood Forest, Carmen studied the Queen Oak, where Robin Hood and Maid Marian are said to have their trysting-place; Robin Hood’s Larder, another giant oak, where legend has it, the outlaws stored their game and the vast labyrinth of caves at the foot of Creswell Crags, where Robin Hood and his men are said to have hidden their horses when the Sheriff of Nottingham was on their tracks.

Back in the studio, Carmen incorporated many of these features of the Robin Hood country into her set design, which then became the subject of a conference between producer Perce Pearce, scriptwriter Larry Warkin and herself before passing it into the hands of the draughtsmen and model makers in her art department. From their blueprints and scale models the construction manager, Gus Walker, was then able to allocate to the various departments concerned the work required to bring the sketch into concrete existence".

|

| Carmen plans Nottingham Square |

Carmen Dillon was without a doubt one of the main reasons Disney's Story of Robin Hood oozed quality. I believe her remarkable talent needs to be highlighted a lot more.

In an interview, Ken Annakin, the director of Robin Hood said of her:

"Carmen was one of the great art directors on the European scene. Not only was she an accomplished painter, but she was able to supervise big set construction and set-dressing, down to the last nail. So much so, that sometimes when I was lining up a shot, I found her a bit of a pain in the ass because she would insist that her designs and her visual conception of a scene must be adhered to, whereas I regarded the sets only as a background for the actors".

|

| Carmen Dillon plans another set |

Annakin went on:

"He [Walt] didn’t stay very long on Robin Hood. He had great trust in Carmen Dillon, who was responsible for the historical correctness. Everything, from costumes to sets to props and he - I’m not so sure why he was so certain - but he was dead right at having chosen her. And she did that picture and Sword and The Rose too. And his reliance was 100%. A director can’t go into every historical detail and so I would check with her also, pretty well on most things. And she would quietly be on the set and if we used a prop wrongly, she would have her say. Mine was the final say, as director, but one couldn’t have done without her ".