*Somtyme I was an archere good,

A styffe and eke a stronge;

I was compted the best archere

That was in mery Englonde.

*A Gest of Robyn Hode

It was during the last quarter of the thirteenth century that the longbow man became recognised as an effective part of the English army. Richard I (1189-1199) preferred crossbowmen on foot in conjunction with cavalry, but during Edward I’s (1272-1307) Welsh wars he discovered the true value of a skilled archer and laid the foundation of the longbow as a military weapon, that was to shock the French between the 1340’s and 1420’s.

Gerald of Wales had recorded, in about 1188 its deadly uses by the men of South Wales, during the Norman invasion of Ireland.

William de Braose also testifies that, in the war against the Welsh, one of his men-at-arms was struck by an arrow shot at him by a Welshman. It went right through his thigh, high up, where it was protected outside and inside the leg by his iron thigh armour, and then through the skirt of his leather tunic; next it penetrated that part of the saddle which is called the alva or seat; and finally it lodged in his horse, driving it so deep it killed the animal.

Quickly realising its potential, Edward I started by combining Welsh and English bowman with awesome effect against the Scots at Falkirk in 1298.

A landmark in the history of archery had been reached in 1252 with Henry III’s Assize of Arms. It confirmed the recognition of the bow by the English and its importance in warfare. And declared that in a time of emergency (posse comittatus) commissioners were to select as paid soldiers, citizens with chattels worth more than nine marks and less than twenty. They should be armed with bow, arrows and a sword. A special clause was included for poor men with less than this who could bring bows and arrows if they owned them. But those living within or near a Royal Forest had to keep their arrows blunt.

There are no surviving bows from the early Middle Ages and only five from the Renaissance, but they are similar in construction. All five are ‘self bows’, that is made from a single stave of wood, shaped in order to use the centre and sap wood and symmetrically tapered. The favourite wood was Spanish Yew or Wych Elm, Elm or Ash. Because of our wetter climate English Yew was courser grained and therefore not as popular.

Bows were made by a craftsman called a Bowyer. First, logs of yew were cut into thin sections called ‘bow staves’. These were then stored for three to four years to ‘season’, before being ready for the bowyer to shape into slender bows. The bow stave is cut from the radius of the tree so that the sapwood (on the outside of the tree) becomes the back and the heartwood becomes the belly. The lighter sapwood (on the outside curve, facing the target) would aid spring, whilst the darker heartwood (on the inside) would aid compression.

The bow strings were made of twine, which in turn, was made from hemp and flax plants. Ash was a popular wood for arrows, although most wood was suitable and the feathers, usually from the grey goose, were stuck on with glue made from bluebell bulbs.

In 1285 Edward I re-enacted the Assize of Arms with his Statute of Winchester ordering that, every man shall have in his house equipment for keeping the peace, according to the ancient assize; that is to say, every man between 15 and 60 years of age shall be assessed and obliged to have arms according to the quality of his lands and goods.

Edward’s Assize ordered that archery should be practised on Sundays and Holidays and thirteen years later, King Edward’s archers concentrated hails of arrows with devastating effect on the Scots during the Battle of Falkirk. In this same year an incident recorded in the “De Banco Roll” gives an excellent description of a bow and arrow used in a murder. A Simon de Skeffington had been shot and killed by a barbed arrow. The wound measured three inches long by two inches wide and was six inches deep. It had been caused by:

….an arrow from a bow, the arrow being barbed with an iron arrow-head 3 inches long and 2 inches broad, the arrow was almost 34 inches long of Ash…….feathered with peacock feathers and the bow being of yew and the bowstring of hemp, the length of the bow being one ell and a half in gross circumference (five feet seven inches long).

In ‘A Gest of Robyn Hode,’ one of the earliest surviving ballads about the outlaw, a knight re-pays Robin a debt:

An every arowe an elle longe,

With pecok wel idyght,

Worked all with white silver;

It was a seemly sight.

* A Gest of Robyn Hode

The advantage of the bow or longbow, as the military version became known, was its relative cheap construction and expandability. Its problem was the training involved to make it an effective killing instrument on the battlefield. So boys from about the age of ten, spent hours in their local churchyard practising at the butts after Mass on Sundays. This compulsory training was essential as the art of drawing a bow took years to perfect. The lightest bow had draw weights of around 100 pounds, the heaviest about 175 pounds, with the bow drawn 'to the ear' (rather than to the corner of the mouth as is common in modern archery). The attachment points for the string were protected by horn ‘nocks’. There was no arrow rest on the handle as on modern bows, with the arrow resting on the index finger. The longbow, often as tall as its owner (sometimes well over 5 ft.), could loose an arrow 180 metres and the best archers could accurately draw and discharge between ten to twelve arrows a minute.

Ascham in ‘Toxophilus’ (1545) wrote, ‘ a perfyte archer must firste learne to knowe the sure flyghte of his shaftes, that he may be boulde always, to trust them.

In 1466 an Act ordered all Englishman, with the exception of judges and clerics, to keep a longbow of their own height and further decreed that every town and village must erect butts at which the citizens were to shoot on Sundays and feast-days, or face a fine of one halfpenny for each failure to do so.

There were three main marks for the archer. The first was the ‘rover’, used in shooting over open ground at uncertain distances. Secondly, the ‘prick’ or ‘clout’ was a small canvas mark with a white circle painted on it and a wooden peg in the centre of the ring. Usually set at distances from 160 to 240 yards ‘prick-shooting’ was intended to teach the archer to be able to shoot as often as necessary over the same distance. The third mark were the ‘Butts’, earthen turfed mounds on which paper discs marked with circles were fixed. They were erected at the public cost in every village up and down the English countryside and their use was frequently enforced to encourage the use of the weapon that brought astonishing victories at Crecy, Poitiers and Agincourt.

Bishop Latimer (1485-1555) was the son of a yeoman, who as a child had been taught how to use a longbow:

In my time my poor father was as delighted to teach me to shoot as to learn any other thing; and so I think, other men did their children; he taught me how to draw, how to lay my body and my bow, and not to draw with strength of arm as other nations do but with strength of body. I had my bow bought me according to my age and strength; as I increased in them, so my bows were made bigger and bigger; for men will never shoot well, except they be brought up to it. It is a goodly art, a wholesome kind of exercise, and, much commended as physic.

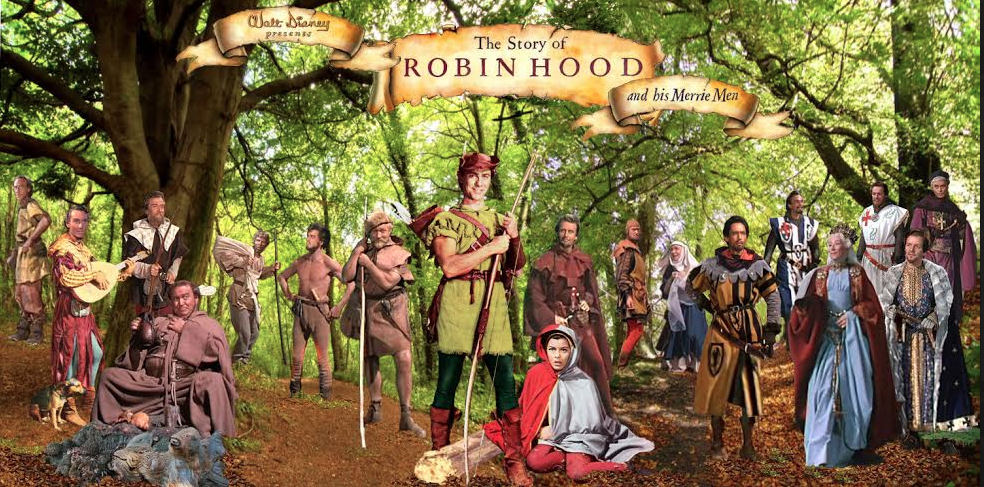

But archery practice became a duty that undoubtedly many tried to evade in one way or another, so to raise the enthusiasm, private matches were set up and archery pageants were organised in local villages. These competitions and games soon became linked with the bold outlaw who became synonymous with accurate shooting of a bow and arrow, Robin Hood.

Philip Stubbs (f. 1583-91) explains how the Summer games incorporated the practice of archery:

Myself remembreth of a childe, in contreye native mine,

A May Game was of Robyn Hood, and of his train, that time,

To train up young men striplings and each other younger childe,

In shooting; yearly this with solemn feast was by the guylde,

Or brotherhood of townsmen.

So the archery practice linked with the summer games and festivals insured the continuing popularity of the outlaw hero.

*Thryce Robyn shot about,

And Always he slist the wand,

And so dyde good Gylberte,

With the wyte hande.

Lytell Johan and good Gylberte,

Were archers good and fre;

Lytell Much and good Reynolde,

The worste they wolde not be.

* A Gest of Robyn Hode

© Clement of the Glen 2006-2007