From an early age, my fascination with history and a deep love for the legend of Robin Hood naturally led me to embark on a quest to uncover the true story behind the legendary outlaw. Over fifty years later, this pursuit has shaped my career and culminated in a successful genealogical business.

The origins of Robin Hood have sparked centuries of debate. Historians and antiquarians have long struggled to find concrete evidence of his existence, with many theories evolving without definitive proof.

One such theory was the pedigree published by William Stukeley (1687–1765). It linked the earls of Huntingdon with the descendants of a man called Ralph Fitz Ooth, who he claimed became lords of Kyme.

When I first encountered this family tree in the 1970s, I was thrilled by the possibility. There he was, Robin Fitzooth, alias Robin Hood! However, this pedigree, first presented in Stukeley's Paleographica Britannica in 1746, has since been thoroughly debunked by scholars like Professor J. C. Holt. They have argued that Stukeley’s claims were not only fabricated but that Stukeley himself, known for his eccentricities and romanticism, may have been more interested in myth-making than historical accuracy.

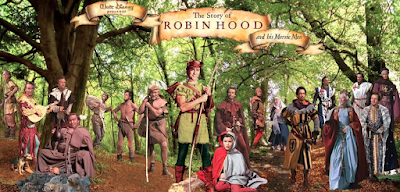

Although scholars have debunked it, the idea that Robin Hood was once an Earl of Huntingdon became firmly embedded in his legend. Centuries later, this version of the tale was embraced by Walt Disney, who depicted Robin as Robin FitzOoth in his 1952 live-action film The Story of Robin Hood.