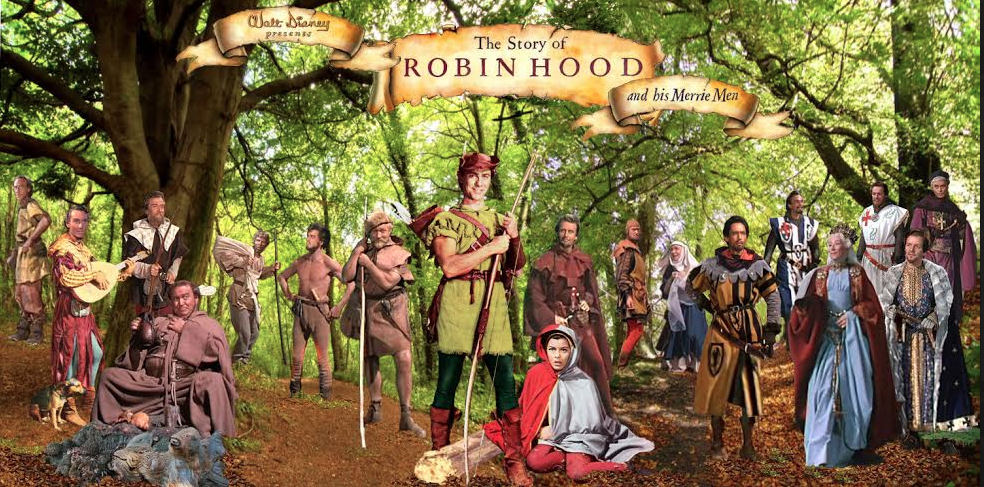

Robin Hood Postcard

This postcard (above) was one of the first pieces of memorabilia I ever bought. It is taken from a publicity still of Walt Disney’s Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men (1952) and shows Richard Todd as Robin Hood and Joan Rice as Maid Marian. Do you have any postcards from this wonderful film?

Carmen Dillon's Robin Hood

|

| Scathelock is put in the stocks |

Neil has been a regular contributor to this blog for many years and shown above is a still that he recently sent to me. It is of course from Walt Disney's Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men (1952). I love seeing these images from my favourite movie. When concentrating on the film's

It was Carmen Dillon (1908-2000) who was given the job of art director on Robin Hood by Walt Disney. She had a fine reputation on both sides of the Atlantic for imagination and artistic flair allied to a practical approach to set design and construction, which had been evident in her art direction of some of the biggest and most highly praised period films made in Britain at that time, including Henry V and Hamlet, for which she won her Oscar.

|

| Carmen Dillon discusses the design of Nottingham Square |

Catherine O'Brien in her article, Carmen Over Came Prejudice

..........And Put On Her Slacks, gives a detailed account of this remarkable woman and her work on Robin Hood:

"Small and neat of figure, with greying hair and light blue eyes, Carmen Dillon was born in Ireland. After she had qualified as an architect, she became greatly attracted by the artistic possibilities of film set design and set out to get a job which would train her in this field. It is strange to reflect that this happened only fifteen years ago and yet at this time no one in film studios would take the idea of a woman art director seriously.

|

| Carmen discussing a castle interior |

Anyone knowing Carmen Dillon, however, would realise that such an attitude would only serve to strengthen her determination to attain her objective. Eventually, she obtained toe-hold in a studio at Wembley, as an assistant in the art department. Even then petty restrictions beset her at every turn. She was not permitted to go on a set in slacks and was forbidden to discuss her work with the men in the studio workshops and stages. After a few weeks of making the best of this difficult situation, Carmen was asked to take over the work of an art director who had fallen ill on the eve of a production. By proving her undoubted talent and aptitude for production design she was able to overcome the prejudice which had hitherto hampered her career.

|

| The townsfolk turn on the Sheriff |

On Walt Disney’s Robin Hood, Carmen was in control of a staff of over two hundred men, who accepted her advice and judgement with the same respect and deference as they would accord to any male art director. Among the technicians, she has earned, through her skill and tact, a reputation for knowing exactly what she wants, without fuss or muddle. She carries all the details of planning and building the sets in her head and has a remarkable knack of foreseeing and thus forestalling building problems.

Before the stage is set for the actors, the lighting cameraman and the director, Carmen plans the work, step by step, with fastidious detail. In the case of Robin Hood, the first step was research, to ensure that the pictorial effect should have a truly authentic 12th-century keynote.

|

| Collecting for the King's ransom in Nottingham Square |

Two of the twenty-five interior sets designed by Carmen Dillon for Walt Disney’s Robin Hood serve to illustrate the immense research and artistry with which she conjured up the background and atmosphere of 12th-century England. One of- Nottingham Square, in the reign of Richard Lionheart-was, constructed both on Denham lot and on one of the studio stages-to cater for both units.

Three sides of an irregular square were surrounded by houses, some half-timbered and all pre-fabricated in the plasterer's shop under the direction of Master Plasterer Arthur Banks. The houses and shops made of plaster and wattle (which was, in fact, the building material of that period) had every appearance of solid antiquity in despite of their backing of tubular steel scaffolding. Most imposing was the Sheriff’s house, with its carved arches and steep outside staircase. Thatching was carried out by one of Britain’s oldest surviving craftsmen in this line Mr A. Gilder of Stoke Poges.

The centre of the square was filled with wattle hurdles and pens in which were enclosed game and produce of every type. By the time the stars, featured players and extras-numbering up to two hundred-had taken their place in the square it was hard to imagine a more convincing reproduction of life in 12th century England. It is in this setting that Robin Hood and his men ride in from the forest to rescue a poacher and a farmer who are suffering at the hands of the Sheriff of Nottingham and succeed in turning the tables on their hated persecutor.

|

| The Outlaws receive a signal |

One of the most important sets in the film is the Sherwood Forest camp where Robin Hood and his Merry Men live in outlawry, in their woodland hideout. Some weeks before the film, Carmen accompanied a research party including producer Perce Pearce, scriptwriter Larry Watkin, and film star Richard Todd to Nottingham and returned laden with photographs of every relic of Robin Hood days, which would help her construct the original setting at Denham Studios.

In what little remains of the original Sherwood Forest, Carmen studied the Queen Oak, where Robin Hood and Maid Marian are said to have their trysting-place; Robin Hood’s Larder, another giant oak, where legend has it, the outlaws stored their game and the vast labyrinth of caves at the foot of Creswell Crags, where Robin Hood and his men are said to have hidden their horses when the Sheriff of Nottingham was on their tracks.

Back in the studio, Carmen incorporated many of these features of the Robin Hood country into her set design, which then became the subject of a conference between producer Perce Pearce, scriptwriter Larry Warkin and herself before passing it into the hands of the draughtsmen and model makers in her art department. From their blueprints and scale models the construction manager, Gus Walker, was then able to allocate to the various departments concerned the work required to bring the sketch into concrete existence".

|

| Carmen plans Nottingham Square |

Carmen Dillon was without a doubt one of the main reasons Disney's Story of Robin Hood oozed quality. I believe her remarkable talent needs to be highlighted a lot more.

In an interview, Ken Annakin, the director of Robin Hood said of her:

"Carmen was one of the great art directors on the European scene. Not only was she an accomplished painter, but she was able to supervise big set construction and set-dressing, down to the last nail. So much so, that sometimes when I was lining up a shot, I found her a bit of a pain in the ass because she would insist that her designs and her visual conception of a scene must be adhered to, whereas I regarded the sets only as a background for the actors".

|

| Carmen Dillon plans another set |

Annakin went on:

"He [Walt] didn’t stay very long on Robin Hood. He had great trust in Carmen Dillon, who was responsible for the historical correctness. Everything, from costumes to sets to props and he - I’m not so sure why he was so certain - but he was dead right at having chosen her. And she did that picture and Sword and The Rose too. And his reliance was 100%. A director can’t go into every historical detail and so I would check with her also, pretty well on most things. And she would quietly be on the set and if we used a prop wrongly, she would have her say. Mine was the final say, as director, but one couldn’t have done without her ".

The Adventures and The Story

Two Robin Hood films. One was made in America and became legendary in its own right. The other was made in England and has almost completely been forgotten. The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men (1952). In this article, I would like to compare these two versions.

In his book The Best of Disney (1988), Neil Sinyard says:

"Nobody would make great claims for the imaginative cinematic qualities of the films Disney made in Britain in the 1950s."

He then goes on to say:

" The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men (to give it its full title) certainly pales in comparison with earlier film versions of the legend starring Fairbanks and Flynn."

" The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men (to give it its full title) certainly pales in comparison with earlier film versions of the legend starring Fairbanks and Flynn."

I am a great admirer of both early versions. I think Warner Brothers The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) truly deserves its iconic status. But, I do have issues with Sinyard over his statement that Disney's Story of Robin Hood lacks 'imaginative cinematic quality'. In my opinion, 'Uncle' Walt's live-action romp through Sherwood stands-up well, alongside Hollywood's Oscar winner.

The Story of Robin Hood was one of the most popular films in Britain in 1952 and would eventually gross over $4,578,000 at the American box office and $2.1. million worldwide. It was the last film to be made at Korda's legendary Denham Studios in Buckinghamshire. The location filming was done in the beautiful countryside of Burnham Beeches. They didn't need to spray the leaves green like their American cousins!

The Story of Robin Hood was one of the most popular films in Britain in 1952 and would eventually gross over $4,578,000 at the American box office and $2.1. million worldwide. It was the last film to be made at Korda's legendary Denham Studios in Buckinghamshire. The location filming was done in the beautiful countryside of Burnham Beeches. They didn't need to spray the leaves green like their American cousins!

Erich Korngold's score for The Adventures of Robin Hood has, of course, passed into cinematic history. It's 'chromatic harmonies, instrumental effects, passionate climaxes—all performed in a generally romantic manner,' have been rightly praised. But, The Story of Robin Hood also had a lush, rousing, symphonic score, played by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and conducted by Muir Mathieson. Its composer was Clifton Parker (1905-1989).

Parker received very little recognition for his film scores in his lifetime, but during his distinguished career, he composed for 50 feature films, as well as numerous documentary shorts, radio and television scores and over 100 songs and music for ballet and theatre. Sadly today, many of his compositions are lost. But, Parker was regarded by film-makers of the time, as ' the composer who never disappoints.' On The Story, he certainly did not!

When comparing the two movies, I believe it is respect for the legend that is important. For me, the research conducted by the Disney team shines through.

When Walt Disney first announced that he was to make The Story of Robin Hood, he received a letter from the Sheriff of Nottingham inviting him to visit the City Library and inspect the collection of over a thousand books of ‘Robin Hood’ lore. Walt Disney replied that he would be unable to go to England until the film went before the cameras, but that he would extend the kind invitation to Richard Todd and his production unit under the supervision of producer Perce Pearce.

|

| The Disney production crew, including Richard Todd in Nottingham |

Walt Disney’s production crew included producer Perce Pearce, scriptwriter Lawrence Watkin, historical advisor Dr Charles Beard and art director Carmen Dillon. Some of the places that the production crew visited included Nottingham City Library, Nottingham Castle, Newstead Abbey, Edwinstowe, Sherwood Forest including Robin Hood’s Larder (now gone) and the Major Oak, Ollerton, Creswell Crags, Nottingham’s Caves, the Salutation Inn and the Trip to Jerusalem Inn.

Elton Hayes had a hit record with, Whistle My Love (1952) from The Story of Robin Hood. In the 1938 Errol Flynn film, the character Alan-a-Dale is merged with Will Scarlet and given the name 'Will o' Gamwell'. This character, played by English actor Patric Knowles, just plucks at a lute in one scene.

One of the strong-points in The Adventures is, of course the iconic sword-fight between Robin (Errol Flynn) and Guy of Gisborne (Basil Rathbone). The shadow of the two characters flickering on the castle walls is a piece of cinematic history.

|

| Errol Flynn as Robin Hood and Basil Rathbone as Guy of Gisborne |

But, The Story of Robin Hood has an equally climactic scene. Sheriff De Lacy (Peter Finch) has gone back on his word as a knight and prevents Robin Hood (Richard Todd) from re-joining Marian (Joan Rice) and the outlaws in Sherwood Forest. As Robin reaches the drawbridge, the treacherous Sheriff seizes a spear from a castle warden and launches it at the outlaw, wounding him.

The outlaw then scrambles over the drawbridge, avoiding being crushed and has to swim across the moat, amidst a shower of arrows - a breath-taking scene in which Richard Todd was nearly seriously injured!

I am sure that fans of The Adventures of Robin Hood will argue that the sheer quality and sumptuous sets and costumes of this classic, raise it well above Walt Disney's live-action version. Once again, I argue that there is little to choose between the two. The costumes and sets were equally as glamorous. Hubert Gregg, who played Prince John in The Story complained that his expensive costume was so heavy he had trouble getting down from his horse:

|

Claude Rains (Prince John), Basil Rathbone (Gisborne) and Melville Cooper (Sheriff)

|

I am sure that fans of The Adventures of Robin Hood will argue that the sheer quality and sumptuous sets and costumes of this classic, raise it well above Walt Disney's live-action version. Once again, I argue that there is little to choose between the two. The costumes and sets were equally as glamorous. Hubert Gregg, who played Prince John in The Story complained that his expensive costume was so heavy he had trouble getting down from his horse:

"The costumes were beautiful, if unnecessarily weighty in their adherence to medieval reality. One cloak was heavily embroidered and lined with real fur: it cost more than a thousand pounds (a good deal of money in pre-inflationary days) and took all my strength to wear. In one scene I had to ride into the town square, leap off my horse and enter the treasury building in high dudgeon.

|

| Hubert Gregg as Prince John in the £1000 cloak |

|

| Prince John (Hubert Gregg) and the Sheriff (Peter Finch) |

Many of the costumes and props from Walt Disney's Story of Robin Hood found their way into later media productions of the legend, including the hugely successful TV series of the 1950s starring Richard Greene.

I could go on and on comparing these two wonderful films. But I would like to finish with a look at the two versions of Robin's beautiful girlfriend, Maid Marian.

Olivia De Havilland's role as Marian was something she was very proud of. Understandably so. Her partnership with Errol Flynn fizzed with electricity and it is claimed that she was in love with him during the filming.

She was described by Milo Anderson, the costume designer on The Adventures, as a strong-minded woman who had her own ideas about things on set and would do research into her roles. It paid-off. Olivia's performance broke the mould of Maid Marian. Before, the character had simply been a love-interest 'walking through lavish sets in a queenly manner.' But Olivia's Marian is fiercely independent and spirited. She is integral to the plot of the film, guiding the outlaws after his capture at the archery contest and attempting to get a message to him about the plot to kill King Richard.

This role of the independently willed Marian would be taken up thirteen years later by a young maid who grew up playing amidst the leafy glades of Sherwood Forest. Joan Rice (1930-1997), only recently propelled into the glittering world of stardom, was personally chosen by Walt Disney to play the part of the outlaw's lover in his Story of Robin Hood."

Sherron Lux in her paper And The 'Reel' Maid Marian, gives Joan's 'Marian' some far-overdue credit:

"Joan Rice is vital to Ken Annakin’s 1952 film for Walt Disney, misleadingly called The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men; it is Marian’s story, as well, because without her, only about half the story would be left. Joan Rice gives us a bright, spunky young Lady Marian, faithful daughter of the Earl of Huntingdon, and loyal friend to her childhood companion Robin Fitzooth (Richard Todd); though he is the son of her fathers head forester, she eventually falls in love with him despite the social barriers. However, Rice’s Marian has a distinctly independent turn of mind. She defies the Queen Mother’s orders and slips out of the castle disguised in a page-boy’s livery, seeking out her friend Robin, who has become an outlaw in Sherwood Forest. Her actions ultimately help prove that Robin and his outlaws are King Richard’s real friends and that Prince John is a traitor."

Joan Rice will always be my favourite Maid Marian.

My comparison of The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Story of Robin Hood was always going to be subjective. But I feel it is about time Walt Disney's version was brought out of the shadows, dusted down and given some rightful praise. To describe The Story as 'lacking any imaginative cinematic quality' is an affront not only to the rich cast of actors who appeared but also to Disney's multi-talented production crew who produced what critics describe as one of the best Technicolor films ever made in Britain. Watch it and see for yourself!

|

| A sumptuous set from Disney's Story of Robin Hood |

I could go on and on comparing these two wonderful films. But I would like to finish with a look at the two versions of Robin's beautiful girlfriend, Maid Marian.

Olivia De Havilland's role as Marian was something she was very proud of. Understandably so. Her partnership with Errol Flynn fizzed with electricity and it is claimed that she was in love with him during the filming.

|

| Olivia de Havilland as Marian and Errol Flynn as Robin Hood |

She was described by Milo Anderson, the costume designer on The Adventures, as a strong-minded woman who had her own ideas about things on set and would do research into her roles. It paid-off. Olivia's performance broke the mould of Maid Marian. Before, the character had simply been a love-interest 'walking through lavish sets in a queenly manner.' But Olivia's Marian is fiercely independent and spirited. She is integral to the plot of the film, guiding the outlaws after his capture at the archery contest and attempting to get a message to him about the plot to kill King Richard.

This role of the independently willed Marian would be taken up thirteen years later by a young maid who grew up playing amidst the leafy glades of Sherwood Forest. Joan Rice (1930-1997), only recently propelled into the glittering world of stardom, was personally chosen by Walt Disney to play the part of the outlaw's lover in his Story of Robin Hood."

|

| Joan Rice as Marian and Richard Todd as Robin Hood |

Sherron Lux in her paper And The 'Reel' Maid Marian, gives Joan's 'Marian' some far-overdue credit:

"Joan Rice is vital to Ken Annakin’s 1952 film for Walt Disney, misleadingly called The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men; it is Marian’s story, as well, because without her, only about half the story would be left. Joan Rice gives us a bright, spunky young Lady Marian, faithful daughter of the Earl of Huntingdon, and loyal friend to her childhood companion Robin Fitzooth (Richard Todd); though he is the son of her fathers head forester, she eventually falls in love with him despite the social barriers. However, Rice’s Marian has a distinctly independent turn of mind. She defies the Queen Mother’s orders and slips out of the castle disguised in a page-boy’s livery, seeking out her friend Robin, who has become an outlaw in Sherwood Forest. Her actions ultimately help prove that Robin and his outlaws are King Richard’s real friends and that Prince John is a traitor."

Joan Rice will always be my favourite Maid Marian.

|

| Richard Todd as Robin Hood and Joan Rice as Maid Marian |

Richard Todd ‘Dashing Young Blade’ (1919-2009)

|

| The grave of Richard Todd |

Richard Todd is buried at St. Guthlac's Churchyard, Little Ponton, in Lincolnshire, England. He died peacefully in his sleep on Thursday 3rd December 2009. His gravestone contains the epitaph, Exit Dashing Young Blade and I think those three words describe his acting career perfectly. For me - and I suspect many of my blog readers -Richard will always be the ‘dashing blade’ Robin Hood!

"As soon as Flesh and Blood was completed, Walt Disney wanted Richard for the name role in his new picture Robin Hood. It is said that Disney chose Todd for the part after one of his own daughters returned from a cinema - a confirmed Richard Todd fan - she had just seen The Hasty Heart, and she kept telling her father that this young British star had everything!

An outdoor man himself, the idea of playing the great adventurer appealed to Richard, but he didn't want to be forced to portray the outlaw as a ‘costumed twelfth century Tarzan’. He wanted to play Robin Hood as 'he' saw the great outlaw. Fortunately, Walt Disney had enough confidence in Richard to allow him his own portrayal and as we all know the picture was a tremendous success.

Robin Hood had its premiere at the Leicester Square Theatre on March 13th, 1952. It was a glittering oppening and raised a large sum of money for a worthey cause. This film has become a classic, and will doubtless be shown for years and years.

Within four days of finishing Robin Hood, Richard flew to the South of France, to play the part of the incurable young gambler in Twenty Four Hours of a Woman's Life”.

Within four days of finishing Robin Hood, Richard flew to the South of France, to play the part of the incurable young gambler in Twenty Four Hours of a Woman's Life”.

|

| Richard Todd as Robin Hood |

Richard Todd represented, as Michael Winner said, “the best example of classic British film acting. He was a very fine actor but his style of acting went out of fashion, which was a pity because his contribution to British movies was enormous.” Winner went on:

“ Richard was also a very, very nice person. He was a good friend and wonderful to work with, utterly professional, very quiet, just got on with it. He was just a splendid person and a very, very good actor”.

Born Richard Andrew Palethorpe-Todd in Dublin, Todd at first hoped to become a playwright but discovered a love for acting after helping found the Dundee Repertory Company in Scotland in 1939.

He volunteered for the British Army and graduated to the position of Captain in the 6th Airborne Division and took part in the famous D-Day landings of 1944 and was one of the first paratroopers to meet the glider force commanded by Major John Howard at Pegasus Bridge; he later played Howard in The Longest Day.

|

| Walt Disney, Richard Todd and Joan Rice |

After being discharged in 1946, he returned to Dundee. His role as male lead in Claudia led to romance and then marriage to his leading lady, Catherine Grant-Bogle. A Scottish accent mastered while preparing for his role in The Hasty Heart proved a useful skill in his later film career.

He won praise for his performance in the film of The Hasty Heart, which included Ronald Reagan and Patricia Neal in the cast. The New York World-Telegram hailed Todd as ‘a vivid and vigorous actor’ and the New York Herald Tribune said his performance ' combined lofty stature with deep feeling, attracting enormous sympathy without an ounce of sentiment.' Todd and Reagan later became close friends.

|

| Richard Todd reading through a script |

Todd was nominated for an Academy Award for the 1949 film A Hasty Heart and starred as U.S. Senate chaplain Peter Marshall in A Man Called Peter (1954). Marshall's widow Catherine said Todd “ was just about the only film actor whose Scottish syllables would have met (her husband's) standards”.

He also teamed up with legendary director Alfred Hitchcock to star in the thriller Stage Fright and went on to play Robin Hood, Charles Brandon (in Sword and the Rose) and Rob Roy for Walt Disney’s live-action film productions in England. His portrayal as the outlaw Robin Hood will certainly never be forgotten on this web site.

Then came one of his best-known roles, playing Royal Air Force pilot Guy Gibson, in the classic war film The Dam Busters and later the epic The Longest Day in 1962, in which he relived the D-Day landings.

In Britain, James Bond author Ian Fleming picked Todd as his first choice to play 007 - but the actor turned down the role because of other commitments and it went to Sir Sean Connery instead.

The veteran star continued to act in the 1980s with roles in British TV shows including Casualty, crime series Silent Witness and sci-fi classic Doctor Who.

He was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1993. Although many of us on this site believe a Knighthood would have been more appropriate!

|

| Richard Todd |

Todd had a son and a daughter from his first marriage, and two sons from his marriage to Virginia Mailer. Both marriages ended in divorce.

His son Seamus from the second marriage, killed himself in 1997, and his eldest son also killed himself in 2005 following the breakdown of his marriage.

Todd said dealing with those tragedies was like his experience of war.

So how do I finish this short obituary to someone I have admired all my life? I suppose the only way is to use a line from Disney’s Story of Robin Hood which sums up for me the character of the great man.

His like you are not like to see,

In all the world again.

|

| The commemorative plaque at Elstree |

To read a lot more about Richard Todd please click here.

Ivanhoe & The Lionheart’s Ballad

I was pleased to recieve a comment recently by Laurence, regarding my article about the ‘medieval' chant used during one of the scenes of Walt Disney’s Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men (1952).

You can view my post here:- The Chant of the Crusaders.

|

| Prince John (Hubert Gregg) watches his brother King Richard leave for the Holy Land |

Laurence says:

“Interestingly, the same theme is used for background music to the prologue in ‘Ivanhoe’, scored, of course, by Miklos Rózsa. It is reputed to be based on a tune written by Richard the Lionheart himself. Rózsa's sleeve notes for 'Ivanhoe' state, “ Under the opening narration I introduced a theme from a ballad actually written by Richard the Lionhearted”.In my opinion, the 1950’s were a golden era for films such as these. Ivanhoe is another of my favourite movies, released the same year as Walt Disney’s live action film The Story of Robin Hood. Our regular contributor Neil Vessey, has a fantastic web site dedicated to Films of the Fifties. Take a look!

MGM’s Ivanhoe (1952) starred Robert Taylor as the Saxon knight, loyal to King Richard the Lionheart who has been captured and ransomed. Also appearing in this epic adventure are Elizabeth Taylor, Joan Fontaine and George Sanders. The film is based on the novel by Sir Walter Scott, first published in 1819.

|

| Ivanhoe lobby card |

Richard the Lionheart’s Ballad

As Laurence says, it was Miklos Rózsa (1907-1995) who scored the music for MGM's Ivanhoe and in 1953 he was nominated for both Academy and Golden Globe awards for his work. Rózsa is known for composing the music for nearly a hundred films.

In 1987 Rózsa described to Bruce Duffie the medieval sources that inspired him to write the soundtrack for Ivanhoe:

“The various themes in Ivanhoe are partly based on authentic Twelfth Century music, or at least influenced by them. Under the opening narration I introduced a theme from a ballad actually written by Richard the Lionhearted. The principle Norman theme I developed from a Latin hymn by the troubadour Giraut de Bornelh. This appears the first time with the approaching Normans in Sherwood Forest. Later during the film, it undergoes various contrapuntal treatments. The love theme for Ivanhoe and Rowena is a free adaptation of an old popular song from the north of France. The manuscript of this I found in a collection of songs in the Royal Library of Brussels. It’s a lovely melody, breathing the innocently amorous atmosphere of the middle ages, and I gave it modal harmonizations. Rebecca needed a Jewish theme, reflecting not only the tragedy of this beautiful character but also the persecution of her race. Fragments of medieval Jewish motives suggested a melody to me. My most difficult job was the scoring of the extensive battle in the castle because the producers wanted music to accompany almost all of it. I devised a new theme for the Saxons, along with a motive for the battering ram sequence, thereby giving a rhythmic beat which contrapuntally and polytonally worked out with the previous thematic material, forming a tonal background to this exciting battle scene. Scoring battles in films is very difficult, and sadly one for which the composer seldom gets much credit. The visuals and the emotional excitement are so arresting that the viewer tends not to be aware that he or she is also being influenced by what is heard.” (Movie Music UK)

|

| Ivanhoe sings King Richard's ballad outside the castle walls. |

As my regular readers know, I have posted many times on various aspects on the life of Richard the Lionheart. He is a king who has always interested me. So I was keen to investigate this ballad that has been attributed to him and used in Ivanhoe.

The Lionheart is Captured

On his way back from the third Crusade in 1192, King Richard I (1157-1199) was captured by Leopold V, Duke of Austria and sent to a strong castle built high on a mountain-slope over-looking the Danube: the castle of Durnstein. Legend states that Blondel, King Richard's faithful minstrel, travelled the length and breadth of Germany in search of his missing lord. He visited castle after castle and outside each one sang the first lines of a song which he and Richard had composed together.

One day while resting in a garden at the foot of a tower in which Richard was held, the king saw him and sang, ‘ for he sang very well- the first part of a song which they had composed and which was known only to the two of them’ . This was the inspiration for the opening scene of the film, Ivanhoe (1952).

Blondel’s Song

In its earliest known form, this story was told in a Rheims prose chronicle written in about 1260. But it wasn’t until the eighteenth century that the legend took off. There was a troubadour known as Blondel de Nesle who lived at the same time as King Richard I. He was a native of Picardy whose work showed the influence of Gregorian chant. Twenty three of his songs have survived. But sadly, there is not a shred of evidence to link him to the legend or that he ever met the Lionheart.

|

| Blondel outside the castle in Durnstein |

So what was this ballad ‘actually written’ by King Richard the Lionheart, that Rózsa used?

King Richard's Ballads?

Two songs do exist that are attributed to King Richard I in early troubadour manuscripts, the ‘ rotrouenge’ said to have been composed in captivity and a ‘sirventes’ aimed at Dauphin of Auvergne. It is impossible to to be absolutely certain that Richard did write them, but the evidence that he was unusually interested in music is overwhelming. Richard was well educated, his upbringing would have included music. His mother was Eleanor of Aquitaine and a generous patron of poets and musicians. Richard grew up almost exclusively in Eleanor’s court. He was surrounded by the poetry and troubadour culture throughout his childhood.

The incredibly beautiful song, written in captivity, Ja nus hons pris, translates as "no man who is imprisoned' and is said to have been addressed to Richard's half-sister, Marie de Champagne, expressing the feeling that he had been abandoned by her and his barons to an unfair fate.

Is this what Rózsa based his opening theme on for Ivanhoe?

Ja Nus Hons Pris

Original Old French

I

Ja nus hons pris ne dira sa raison

Adroitement, se dolantement non;

Mais par effort puet il faire chançon.

Mout ai amis, mais povre sont li don;

Honte i avront se por ma reançon —

Sui ça deus yvers pris.

II

Ce sevent bien mi home et mi baron–

Ynglois, Normant, Poitevin et Gascon–

Que je n’ai nul si povre compaignon

Que je lessaisse por avoir en prison;

Je nou di mie por nule retraçon, —

Mais encor sui [je] pris.

III

Or sai je bien de voir certeinnement

Que morz ne pris n’a ami ne parent,

Quant on me faut por or ne por argent.

Mout m’est de moi, mes plus m’est de ma gent,

Qu’aprés ma mort avront reprochement —

Se longuement sui pris.

IV

N’est pas mervoille se j’ai le cuer dolant,

Quant mes sires met ma terre en torment.

S’il li membrast de nostre soirement

Quo nos feïsmes andui communement,

Je sai de voir que ja trop longuement —

Ne seroie ça pris.

V

Ce sevent bien Angevin et Torain–

Cil bacheler qui or sont riche et sain–

Qu’encombrez sui loing d’aus en autre main.

Forment m’amoient, mais or ne m’ainment grain.

De beles armes sont ore vuit li plain, —

Por ce que je sui pris

VI

Mes compaignons que j’amoie et que j’ain–

Ces de Cahen et ces de Percherain–

Di lor, chançon, qu’il ne sunt pas certain,

C’onques vers aus ne oi faus cuer ne vain;

S’il me guerroient, il feront que vilain —

Tant con je serai pris.

VII

Contesse suer, vostre pris soverain

Vos saut et gart cil a cui je m’en clain —

Et por cui je sui pris.

VIII

Je ne di mie a cele de Chartain, —

La mere Loës.

Translation:

I

No prisoner can tell his honest thought

Unless he speaks as one who suffers wrong;

But for his comfort as he may make a song.

My friends are many, but their gifts are naught.

Shame will be theirs, if, for my ransom, here —

I lie another year.II

They know this well, my barons and my men,

Normandy, England, Gascony, Poitou,

That I had never follower so low

Whom I would leave in prison to my gain.

I say it not for a reproach to them, —

But prisoner I am!III

The ancient proverb now I know for sure;

Death and a prison know nor kind nor tie,

Since for mere lack of gold they let me lie.

Much for myself I grieve; for them still more.

After my death they will have grievous wrong —

If I am a prisoner long.IV

What marvel that my heart is sad and sore

When my own lord torments my helpless lands!

Well do I know that, if he held his hands,

Remembering the common oath we swore,

I should not here imprisoned with my song, —

Remain a prisoner long.V

They know this well who now are rich and strong

Young gentlemen of Anjou and Touraine,

That far from them, on hostile bonds I strain.

They loved me much, but have not loved me long.

Their plans will see no more fair lists arrayed —

While I lie here betrayed.

VI

Companions whom I love, and still do love, Geoffroi du Perche and Ansel de Caieux, Tell them, my song, that they are friends untrue. Never to them did I false-hearted prove; But they do villainy if they war on me, —While I lie here, unfree.

Click here to hear Ja Nus Hons PrisTell them, my song, that they are friends untrue.

Never to them did I false-hearted prove;

But they do villainy if they war on me, —

While I lie here, unfree.VII

Countess sister! Your sovereign fame

May he preserve whose help I claim, —

Victim for whom am I!VIII

I say not this of Chartres’ dame, —

Mother of Louis!

|

| Ivanhoe (Robert Taylor) sings to King Richard the Lionheart |

My Heart Was A Lion

As Ivanhoe (Robert Taylor) rides past several castles, in search of his king, he sings:

My heart was a lion, but now it is chained,

Far do I travel, and will travel and sing

I travel, I travel in search of my heart

I vowed me a vow and I pledged this to be,

Far will I travel until thou art free.

I think John Haines, in his book, ‘Music in Films on the Middle Ages’, sums it all up very well:

“As it turns out, ‘My Heart Was A Lion,’ is not based on any surviving medieval melody. It does not even occur in Sir Walter Scott’s ‘Ivanhoe.’ It does, however, resemble a modern folk song. Both music and text are apparently new to the 1952 film. It is possible that someone other than Rózsa wrote the music for this song. In the composers sketches for the film, dated November 1951 to January 1952, the music for ‘My Heart Is A Lion’ is nowhere to be found. If Rózsa did not write the song, then quite possibly his orchestrator, fellow Hungarian Eugene Zador - whose daughter once accused Rózsa of not giving enough credit to, ‘young former friend and colleague, the glorified copyist’ - made it up.

Whoever composed it, the song exhibits a few vaguely medieval touches, namely its use of a minor scale and its stepwise approach to cadences. But, in the main, it is a patently modern creation. . .The minstrel song in Ivanhoe bears only the slightest resemblance to the medieval ‘Ja Nus Hon Pris’. The word ‘chained’ vaguely matches Richard’s description of himself as a prisoner (hons pris), but that is all. And its melody has little to do with the music that survives in medieval manuscripts for ‘Ja Nus Hons Pris.’ In short, rather than medieval influences, Ivanhoes’s horseback song bears the marks of modern musical traditions, including that of a singing cowboy”.

John Haines: Music in Films on the Middle Ages Routledge (2013)

Many thanks to Laurence for getting in touch.

Many thanks to Laurence for getting in touch.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)