Born in Cricklewood, north west London on 25th October 1908, Carmen was the youngest of six children-two boys and four girls. Two of her sisters were also to become famous, Tess Dillon became head of the physics department at Queen Elizabeth College, London University and Una Dillon founded the first Dillons bookshop in London’s Tottenham Court Road in 1936.

After attending New Hall Convent in Chelmsford, Essex, Carmen went on to win an Architectural Association Scholarship.

I loved architecture not so much as a great classic thing, but I loved houses, whether ugly or not. I wanted to know how people lived, where they lived, what they did and how they decorated their homes. I particularly enjoyed the historical study of architecture.

But in her spare time she was becoming vey interested in the world of amateur dramatics and soon became involved both as a designer and actress in local productions. At that time, Carmen had been working in Dublin as an architects assistant, until she moved to London where she was eventually offered a job as an assistant art director and set designer at the Wembley Studios for Ralph Brinton making, ‘Quota Quickies’. She later described the B-film movies at Fox British as, rotten little old films, but very exciting and great fun .

Carmen recalls her early days at the film studios:

I just drifted in, I think, and for a long time I was the only female art director in the country. My mother was delighted, though, that I was going into films in some capacity. That was really quite progressive of her to be encouraging me to go into films in the 1930s.

During the early war years, Carmen moved to Denham Studios where she started her long association with Two Cities and Rank and became Britain's first and only female art director for more than forty years.

First I would read a rough outline of the story and try to imagine the kind of settings and do some rough sketches. You always had lots of talks with the director to be sure you both had the same ideas about the look and mood of the film. Then the draughtsman would make the working drawings and the sets would be based on these.

"It was my idea to do it that way," Carmen later said.

The backdrops dissolve when we reach the gritty Battle of Agincourt, then we are gradually brought back to the theatre for the final act. With a limited budget and restrictions this Technicolor film significantly proved a massive hit and morale booster in war torn Britain. Carmen was nominated alongside Paul Sheriff for an Oscar in 1947 for Best Art Direction-Interior Direction in Colour.

Her Oscar finally came for Best Art Direction and Set Direction in Laurence Olivier’s second film as director, the 1948 version of Hamlet, which she shared with Roger K Furse. This production was filmed by Olivier in high contrast black and white and is strikingly different to the extremely colourful Henry V. The mood is sombre and claustrophobic, with much use by cinematographer Desmond Dickinson’s deep focus. The camera creeps through the long dark atmospheric settings, along the bare ancient walls and up the long shadowy, winding staircases, past the huge pillars and repeating arches. Using Olivier’s metaphor that, ‘Hamlet is more like an engraving than a painting,’ Carmen and Roger Furse manage to frame the characters in a geometric minimalistic and detached way.

Hamlet became not just the first British film but the first non-American film to win the Oscar for Best Picture along with Best Actor (Olivier) Best Art Direction and Best Costume Design.

Olivier’s conception of "Hamlet" as an engraving has been beautifully executed by Roger Furse and Carmen Dillon. Sets have been planned as abstractions and so serve to point the timelessness of the period. The story takes place anytime in the remote past. This conception has dominated the lighting and camera work and has made the deep-focus photography an outstanding feature of the film.

(Variety May 12 1948)

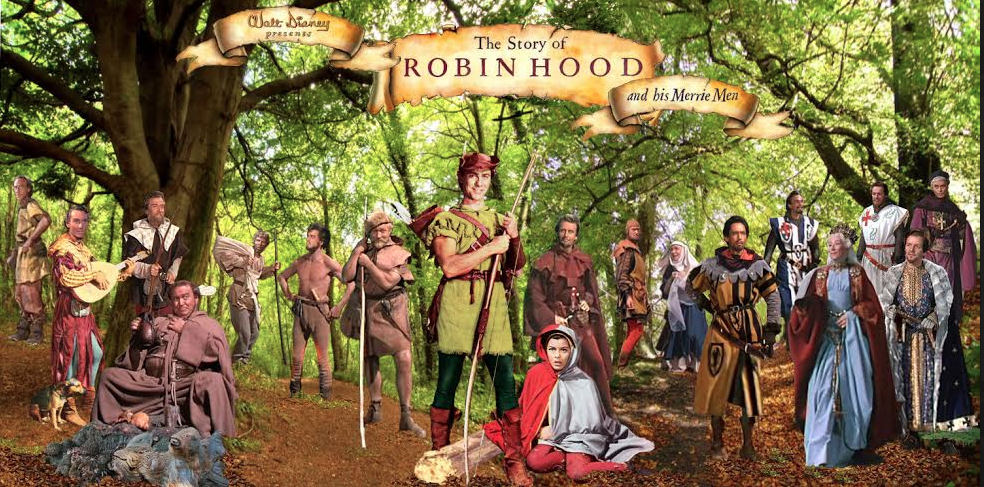

After working as Art Director on many notable films, including The Browning Version (1951). Carmen Dillon’s extensive research and beautifully constructed historical sets continued to be in demand by producers in particular for The Importance of Being Earnest (1952) (which was nominated for a BAFTA and the Venice Festival prize ) and of course Walt Disney’s The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men (1952).

Ken Annakin remembers the start of filming at Denham Studios:

Two of the stages were over two hundred feet long, and I gathered from Carmen Dillon, the art director assigned to Robin Hood, that both stages would be completely filled. One with Robin Hood’s camp in Sherwood Forest, and the other with Nottingham Castle, complete with moat.

Carmen was one of the great art directors on the European scene. Not only was she an accomplished painter, but she was able to supervise big set construction and set-dressing, down to the last nail. So much so, that sometimes when I was lining up a shot, I found her a bit of a pain in the ass because she would insist that her designs and her visual conception of a scene must be adhered to, whereas I regarded the sets only as a background for the actors.

She continued working for Walt Disney on other historical live-action movies including The Sword and the Rose (1953) Rob Roy, the Highland Rogue (1953) and Kidnapped (1960) But:

They were very keen on having a storyboard and that was very trying. You had to pin down every shot for every scene; it was good for you as a discipline, but it wasn't the way I enjoyed working.

During her distinguished career, Carmen was to work on many of the finest British films and was continually favoured for her set design by Laurence Olivier, Anthony Asquith, David Lean and Joseph Losey. Including:

Richard III (1955)

The Iron Petticoat (1956) Checkpoint (1956)

The Prince and the Showgirl (1957)

A Tale of Two Cities (1958)

Accident (1967)

The Go-Between (1971)

Lady Caroline Lamb (1973)

Julia (1977)

During the making of the Prince and the Showgirl the unit assistant, Colin Clark described in his book what it was like working with Carmen:

The art director is a small, intense lady with short grey hair, cut like a man's. She is Carmen Dillon who works with a set dresser called Dario Simoni. Together with Roger Furse, they are responsible for the "look" of the whole film. They are all completely professional and only think about the scenery, and the props and the costumes. They didn't even glance at Marilyn Monroe when she walked in to look at the set for a moment last week, even though MM was quite excited by the whole thing.

Looking back at her career as a woman in a male dominated movie industry, she said:

When I was young and trying to get into films they were very against having women in films at all.”

Carmen didn’t enjoy making A Tale of Two Cities (1958) and later described it as a ‘rotten film, very poor, I’m ashamed of it.’ But she did confess to having a great deal of fun making the ‘Carry On’ films.

In 1977 Carmen worked with Gene Callahan and Wily Holt on production design for Fred Zinneman’s Julia starring Jane Fonda and Vanessa Redgrave. Their art direction was nominated for a BAFTA and the movie itself was nominated for 11 Oscars and won 3. With simple clean lines, Carmen’s versatility in design, captures the whole spectrum of emotions in this very powerful movie and received much critical acclaim.

The period environment, brilliantly recreated in production design, costuming and color processing, complements the topflight performances and direction.

(Variety)

Carmen retired from the world of film making in 1979 and died in Hove, Sussex on 12th April 2000.

With a film one has to live with your draughtsmen much more, living with the work, the craftsmen and everybody all the way through. Whereas on the stage, however much one pours oneself into it, it is "Goodnight dear, see you some time". When one is working on a film one is influenced by the cutting, music - everything. It is much more alive. So, I suppose in a very selfish way I wanted to be "in on it".

(Carmen Dillon)

© Clement of the Glen 2006-2007